Parts, parcels and people – these three words pretty much summarize the biggest and sharpest pain-points that have come in sharp focus as global supply chain convulsions continue in the aftermath of the onset of the covid19 pandemic.

Sometime missing parts can make a hole in your plans to ship product. However, if parts shortages are chronic and unrelenting, it inexorably leads to big holes in a company’s revenue. Left unchecked, it can get quite grim.

This article is focused on Parts and cursorily touches on the “people” aspects.

Parts are super critical. For Product companies the sum-total of all parts is what make the product whole, and ready to make and ship.

Parts shortages, especially those that have a big impact across many products are painful – economically, and what your logo stands for to the markets it serves. And it needs to be attended to quickly but carefully.

“A major Planning dilemma”: of wait & wants – A short story, an outsized impact

First let’s start with a story (fictional) based on real-life events.

Its Q1, 2020, and the pandemic has hit the world – first landing in a few countries, it soon spreads like a forest fire throughout the world. In its wake, it leaves ports, factories and other nodes and links of the global supply chain frozen out.

Now, let’s hone in on one industry – the Automotive industry – that’s been recently feeling the tailwinds of growing consumer demand.

Jill, (fictitious name) head of Materials (parts, raw materials) Planning and Tier1 Supply, is feeling anxious. She brings this up again and again with her supervisor – the SVP of Operations at AutoMax1 – a traditional automaker (OEM) that’s been turning its fortune around over the last year or so.

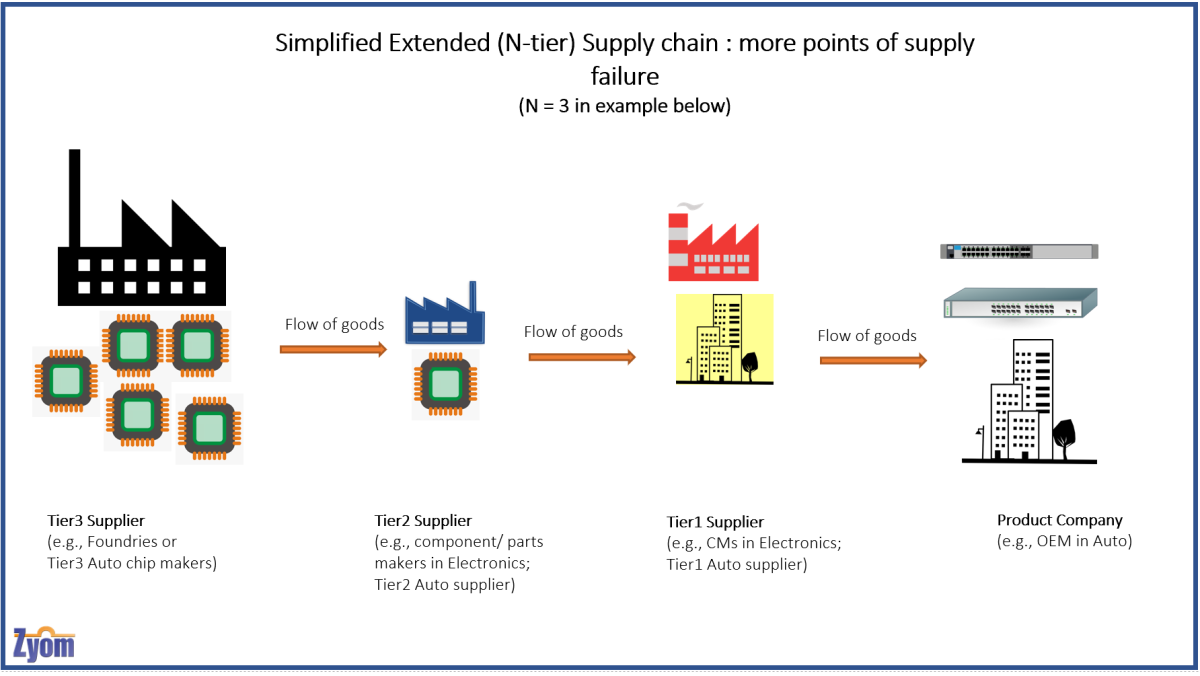

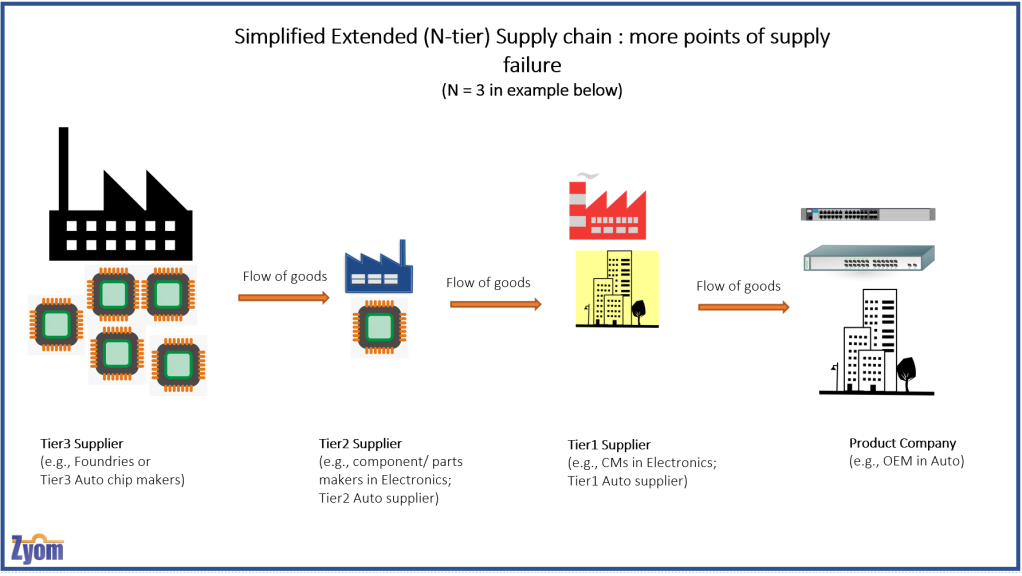

A simplified graphical representation of an extended supply chain with multiple tiers of supply is shown here for reference (Auto supply chains are extended, multi-tier manufacturing supply chains, excluding distribution-only nodes)

Jill – “..Bottom has fallen out of the demand .. what should we do with the open P.O.s to the Tier1 suppliers?”

After quick deliberations, spreadsheets and even looking at systems, a decision is made.

Managers (across functions) – “Let’s just cancel the orders”.

Jill – “All the open orders, or a few?”

Pause. More discussions. Deliberations.

Managers (with inputs from senior leaders) – “All”

..

All Q1 and a big chunk of Q2, 2020 turns out be worst case scenario for demand, as predicted.

Auto industry demand crashes.

Other peers of Jill, and the SVP Ops at other car companies largely take similar or same actions.

..

Its late in Q2, 2020, and an anxious Tier 2 chipmaker calls in and pitches a contrarian scenario –

Tier 2 chipmaker – “Demand’s picking up .. it may pick up too fast .. we don’t know yet. Do you want to reorder (your chips)?”

Again, long pause. Jill is not sure. SVP of Ops is torn. Even management is at sea.

Finally, they decide – “no Thanks .. we’ll wait”.

Not all agree, but they are not the assertive voice/s.

..

Its late in Q3, early on in Q4, 2020 and demand is indeed picking up.

Exciting news for AutoMax1 management? Not really.

Jill and SVP of Ops are super anxious. They may have shot themselves on both their feet with their decision a few months ago.

They have already been testing the waters, started communications with the Tier1s and some key Tier2 suppliers – the ones that make the microcontrollers, or get it manufactured by the Foundries. These are the chips that go into nearly everything in their cars.

Suppliers have NO inventory. Nothing meaningful for a very long time – months, probably quarters.

And the foundries are not heeding their (the Tier2’s) calls for help either.

AutoMax1 gets their COO (even the CEO’s ready) on the line with the Foundry chief.

COO – “You’ve gotta help us out .. we need to ramp up and need these chips now.. This can’t wait a week let alone the months that you are quoting us”.

Chip Foundry Chief – “Sorry, we are really super booked. We cannot even fulfill all open orders from (our larger) consumer electronics companies.”

“They came way before you .. placed hard orders, and reserved capacity”. In effect, giant chunks of capacity are now gone.

AutoMax1 COO – “what can you do?”

Foundry – “Nothing really in the near term .. nothing material for the next 2-3 quarters.. we’re nose to the grindstone getting these orders shipped .. we’ll call you as soon as we see capacity open up ..”

A Famine

And that pretty much sums up what happened to a giant chunk of the auto sector in the 2nd half of 2020, and Q1, 2021, leading up to the President of the US and heads of state getting involved in ‘battling the Auto chip shortage problem’. Nothing helped. Not for the near to fuzzy midterm[1].

The chip industry, a notoriously cyclical industry, with high booms and terrible busts in demand and pricing, with its gigantic, capacity-intensive fabrication plants (fabs) were booked solid with orders from the consumer electronics industry, that came way ahead of these auto orders.

In fact, these competing orders had a higher priority for the right economic reasons – higher margin consumer electronics orders, that use leading edge technology, versus the Auto industry that’s been on the lagging edge for a while. Lagging, despite the move to EVs accelerating – with Tesla et al. clearly gaining ground in the auto-market through their simpler, super popular EVs. Anyway, that’s for a later write-up, not this one.

What happened next is quite well known. A mini-nuclear winter of sorts for the auto industry..

Thanks to chip shortages painful shutdowns ensued, first by car category (with lower or lower margin demand), then multiple categories, then manufacturing plants, then entire groups of plants and virtually most (traditional) auto-maker plants across giant swathes of the US and Europe.

A Feast (almost) in other places

Meanwhile, over in Japan, Toyota is humming along – and by the end of Q1, 2020 even guided a rosier shipments (Revenue) picture for the whole year.

Tesla, a tiny dot in the auto-manufacturing firmament a few years ago, is growing shipments every quarter – still small compared with traditional car industry volumes – but ramping up seriously (roughly 80% volumes year over year). And they seem to be unfazed too. In fact, Q4, 2021 turns out be eye-popping one – Tesla shipping way more than anyone would have predicted.

And that’s what brings us to the $500 Billion dollar question[2].

What happened?

How could Toyota, a large automaker, be resilient throughout 2020 and early 2021 (some of the pixie dust appears to have worn off since)?

It’s after all a traditional automaker with plenty of gas-guzzlers in its portfolio (i.e., cannot participate in the EV spike in market demand).

What has Tesla learned about making cars, parts and sourcing for their factories which their 100+ year rivals with their huge volumes (i.e., purchasing power) have not?

Learnings

First off – No, this article is not about the auto industry, the EV leadership of Tesla etc.

This article is about finer operating points (operations planning & execution) that many, even with decades of supply chain and planning experience, appear to have missed.

A clear disclaimer – what’s written here is a hindsight-based learning, a post-mortem, not specific to any industry. Sincere attempts have been made to remove all hindsight bias.

No claims are being made by the author (or teams he works with) that they could have done a better job at ‘predicting’ the rapid downswing in the ‘early pandemic’ days, and the rapid upswing in demand soon after, for those sectors that faced what’s been described above (including the auto industry).

This article focuses on some key supply chain operating principles and practices that may have to be dusted off, looked at afresh if not challenged outright, and other evolving approaches to managing manufacturing-intensive supply chains.

Here are a few –

- Identify key parts – This is not a straightforward exercise of looking at your highest dollar parts.

What multi-variable analysis needs to be done to determine “key” parts?

What additional ‘decision filters’ should be applied? - Use “lean signaling” not lean inventory approach especially for key parts – Ideally disintermediate your supply chain (i.e., reduce number of tiers) at least for the newer products, if you can. In either case – with long, extended supply chains (Traditional automakers like GM, Ford, VW et al.) or shorter chain ones (like Tesla), ask this:

How can I rapidly collaborate (not just communicate) with my significant N tiers of supply (where N is 1, 2 .. whatever)?

What are best (if not optimal) inventory levels for key parts made by the TierN supplier?

Is there a better way than legacy tools (EDI, spread-sheets like MS-Excel, Google sheets, etc.)?

Are internet-based supplier portals adequate? - Determine inventory levels for key parts – Toyota built strategic buffers for their key parts where and when needed. Toyota instructed its suppliers to carry months of inventory where previously they used to carry weeks’ worth only, the latter being in line with lean principles that is core to Toyota operations.

How to determine what inventory levels are right? How & when to adjust?

What analysis needs to be done rapidly? Which analysis can have longer cycle times? - Build real ‘relationships’ with suppliers (Tier2 and their sources, as needed) – Component (part) makers would love to work directly with the product makers (the ones whose logo goes on the product). This could be especially critical for mid-size and smaller companies that cannot command part makers’ attention via large, strategic buys. They know full well that one such wrong decision can put them into a deep working capital hole for a long time, or push them into extinction.

Which component makers? What meaningful processes can you collaborate on?

What are “must-haves” to make sure collaboration works (data, process, decisions, metrics)? - Plan for business continuity all the time – Business Continuity Planning (BCP) is not just for isolated worst-case events, such as the Fukushima disaster that froze auto supply chains, Taiwan earthquake that rattled consumer electronics – including the large behemoths. BCP is an ongoing process effectively used by those that are succeeding to secure the supplies needed, no matter what.

How will you do this (process, people, parts, partners)?

What parts to focus on? Which products?

Which ones to defocus from? - Understand your key parts very well (passing acquaintance isn’t enough) – Get to know the technologies that go into your key parts, especially complex/ line-stopping ones very well (e.g., batteries for EV makers, microcontrollers for automakers, WiFi chipsets for wireless equipment makers, etc.). Build the technology skills needed so you can turn on a dime and change product design if a part’s supply shortage becomes persistent.

Which technologies (chip design, etc.)? What skills? How to motivate learning? - Design for resilience and responsiveness – Back to the story above:

Jill, the planning lead and her supervisor, the SVP of Ops were at a standstill and could not take decision to increase the supply even when the chipmaker dropped hints. There could be many reasons. Here are a few –- Role of planning in the org: does it have the right level of visibility and sway with the executive team? i.e., could they have pushed a more aggressive supply plan without being worried about untoward consequences (i.e., losing faith of the management, or worse)

- Skills – Has Master Planning/ MRP/ Capacity Planning and related supply side operations planning skills been rethought through and retooled, especially for extended and evolving supply chains? Has demand planning been rethought through? Planning must be thought through for end-to-end Demand and Supply Planning. And then rethought through periodically in light of changes.

- People-centered Processes and collaboration – Did AutoMax1 have a comprehensive process (including S&OP) which they could use to avoid bias? How good was their supplier collaboration to ensure clear supply signals – strong and weak signals (e.g., chipmaker signals noted above)?

- Tools – What’s the burden of legacy? Were they going to war with bubble gum and duct-tape to put together their plans? Many legacy systems are a lot clunkier, difficult to use and error-prone, given cloud and internet-native tools can be designed and tailored for operations. And they suck up not only time but a lot of people too.

- System – Were they educated about responsiveness which is not a demand side or supply side approach but an end-to-end approach? End-to-end from Demand through to Supply planning – not as ‘islands of Planning’. Execution signals have to be inbuilt into Planning.

- Scaling mindset – A scaling mindset means looking at the future to be an opportunity to grow in a planned manner. How do planners avoid the “hunker-in-the-bunker” mindset that’s the default, especially in operations planning when faced with extreme uncertainty like what happened at the onset of the pandemic – circa Q1, 2020?

- Role of planning in the org: does it have the right level of visibility and sway with the executive team? i.e., could they have pushed a more aggressive supply plan without being worried about untoward consequences (i.e., losing faith of the management, or worse)

Question Assumptions

When faced with unprecedented uncertainty past assumptions have to be questioned.

Good planners know every plan has in-built assumptions.

Great planners know when to question those assumptions out aloud, so management gets it loud and clear. In the above case of Jill and AutoMax1, did they listen to the skeptical, dissenting voices among procurement and supply planners. The planners/ procurement team members may want to understand the signal better from the supplier/s (the chipmakers saying demand is ‘perking up’) before giving their procurement plans a massive haircut.

Great Operations leaders know Planning is a critical ongoing process that requires smarts and creativity, and focused attention of the top management (CEO, COO, Leaders of Operations and Sales, Products).

and,

The more inputs the better, especially from outside the 4-walls of the company, e.g., Sales channels, Suppliers, et al.

Most importantly, the age-old truism – not to be wedded to “a Plan”.

Plan, by its very nature is a point-of-time output of the process and needs to keep changing to support smart execution.

While nothing is better (for planners and senior strategists) than having a “run rate” product base to plan, those deep into planning and its subsequent execution, and have seen a few seasons (i.e., are experienced) know that ’stasis’ (standstill) is the absolute opposite of good planning – the wrong place to be. It’s after all a “rate”, i.e., change over time.

Companies that use this time of uncertainty to upgrade their team’s skills and equip themselves with better processes and systems based on learnings above will have all the pieces in place to go for a stronger rebound when demand turns around, and catch the downdraft in their demand much earlier, preventing grave preventable losses (E&O among others).

[1] Derivative of estimates the current size of the chip industry and the auto-industry losses

[1] Estimates vary from 2-3 quarters to 6-8 quarters out from late 2021

Acknowledgments:

The author would like to thank Colin Todd and Fred Harried for some of the learnings mentioned, and to all the (customer) colleagues at Cambium Networks for in-depth discussions and working sessions with Zyom on some of the topics mentioned in the article; All of the above contains copyrighted materials from Zyom Inc. Please acknowledge this when using any of the content.